News

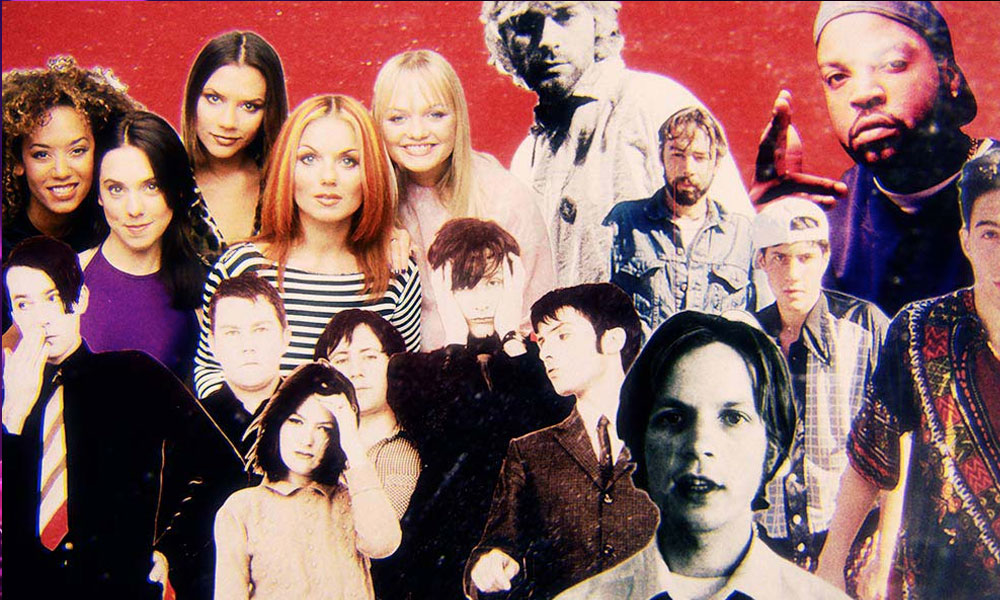

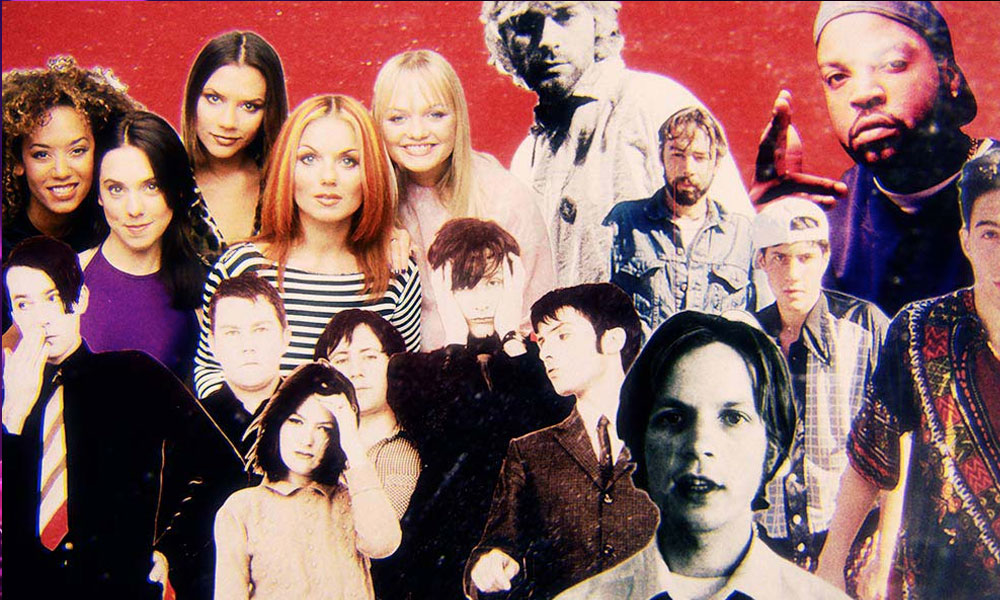

The 90s: The Decade That Doesn’t Fit?

In A Hard Day’s Night, the exceptional madcap 1964 film 1964 starring The Beatles, a reporter asks Ringo Starr, “Are you a mod or a rocker?” She’s referring to the long-warring British musical subcultures, also captured with anxious sincerity a decade later in The Who’s Quadrophenia. The Beatles’ drummer replies with the rather deft portmanteau, “Um, no, I’m a mocker.” The joke being: there’s no way you could be both.

But, 30 years later, in the broad-stroked soundscape that was the 90s music industry, such posturing would look preposterous. The beauty of that decade was that you could be mod, rocker, hip-hop explorer, R&B fan, and country fan – all at the same time. Because the notion of what popular music was had shifted so radically.

While you’re reading, listen to our 90s Music playlist here.

Along came grunge

The biggest curveball that 90s music threw us was, of course, grunge. In the lead up to its inflection point (Nirvana’s Nevermind), guitar-based music roughly fell into three categories: alternative rock, classic-rock standbys, and an already-dimming hair metal scene. It was so lost that 1989 also marked the curious year that Jethro Tull won the best hard-rock/metal Grammy.

Still, at that time, the impact of MTV as the arbiter of youth culture could not be understated. The video for Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” quietly premiered on 120 Minutes, the network’s late-night stepchild, and was almost exotic in its betrayal of the channel’s visual conventions. It was dark, cynical, and so squarely “I don’t give a f__k” in a way that the industry’s self-aware harder rock acts fundamentally were not. But what makes Nirvana such a great microcosm of 90s music was that their sound was not singular in scope. It referenced everything from punk to garage rock to indie pop to country and blues.

Heavy metal didn’t disappear; it just reconfigured itself. The more formidable acts (Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, Aerosmith) transcended fads, becoming stadium bands. Still, for the most part, rock fans diverted their attentions to grunge, with Nevermind and its follow-up, In Utero, serving as a gateway to other bands related to the scene: former labelmates Mudhoney, the metal-inspired Soundgarden, classic-rockers-in-the-making Pearl Jam and the gloomier Alice In Chains. Not to mention non-Seattle groups Bush, Stone Temple Pilots, and a pre-art rock Radiohead – all essentially distillations of the above.

Grunge was resoundingly male-dominated. Regardless, Hole (fronted by Cobain’s wife, Courtney Love, a provocateur with a propensity for stage-diving) managed to benefit greatly from grunge’s popularity. The group’s breakthrough album, the presciently named release Live Through This, dropped in 1994, a mere week after Cobain’s death. Celebrity Skin, its 1998 follow-up, ended up being their best-selling album.

Girls to the front

Most female-fronted rock bands didn’t chart as well, but they did deal in a cultural currency that produced a vibrant feminist-rock scene. Hole drew attention to Love’s contemporaries, including Bikini Kill, Babes In Toyland, Bratmobile, and, later, Sleater-Kinney. Then there was L7. All flying-V riffs, head-banging hair, and “screw you” lyrics, L7 (along with Mudhoney) helped pioneer grunge before grunge broke. And after it did, the group’s 1992 album, Bricks Are Heavy, won acclaim for skillfully toeing the line between the grunge, alternative, and riot grrrl worlds.

Towards the decade’s end, a rise of feminism (and female spending power) in 90s music would trickle up the pop charts. This led to an explosion of multi-platinum singer-songwriters: Sarah McLachlan, Alanis Morissette, Sheryl Crow, Lisa Loeb, Paula Cole, Fiona Apple, Jewel, and the lone woman of color, Tracy Chapman. All of the above (less Morissette) also appeared on the inaugural Lilith Fair tour, McLachlan’s answer to Lollapalooza. It became the best-selling touring festival of 1997.

Counterculture goes mainstream

The larger impact of grunge on 90s music was that it normalized what was once deemed countercultural. Suddenly, middle-of-the-road music listeners were nudged towards exploring what was once considered the domain of indie-music fans, who initially viewed these newcomers as interlopers. Sonic Youth – idols to countless punk bands, including Nirvana, who had opened for them in Europe just before Nevermind exploded – were finally getting radio and MTV airplay. Pixies and R.E.M., already highly respected in the underground, also grew their fanbases, alongside like-minded newcomers such as Pavement, Elliott Smith, Weezer, and Beck.

Meanwhile, the louder alt.rock scene assumed the space left by heavy metal. Industrial music’s Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson, rap-rock’s Rage Against the Machine and Faith No More, the funk-centric Red Hot Chili Peppers and Primus, as well as the transcendent rock of The Smashing Pumpkins and Jane’s Addiction – all capitalized on the new thirst for angst. In this new environment, even a reissue of “Mother,” by the dystopian goth-metal beast Glenn Danzig, became a hit. Perry Farrell, Jane’s Addiction’s eccentric frontman, became a nexus for this phenomenon in 90s music when he created the then-quixotic Lollapalooza festival (its name a Webster dictionary deep cut meaning “extraordinarily impressive”) in the auspicious year of 1991.

After a decade of jock-versus-nerd narratives, being weird became cool, with grunge’s influence permeating into the aesthetics of fashion. Movies such as Cameron Crowe’s Seattle-centric Singles, Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites, and Allan Moyle’s Empire Records jumped on board to celebrate the virtues of outsiders.

As the trajectory of 90 music continued to be reshaped by grunge, the genre itself began to peter out by the middle of the decade. Some influential bands struggled with catastrophic substance-abuse issues. Others felt a disenchantment with becoming part of the establishment they worked so hard to surmount. The progenitors that did survive – Soundgarden and Pearl Jam, for instance – switched up their sounds. The latter went a step further: they simply stopped the machine by refusing to make music videos. And in an even more gutsy move, Pearl Jam refused to work with the events behemoth Ticketmaster.

The rise of Britpop

In the UK, grunge’s chart-takeover of the early 90s created a backlash in the form of Britpop. It’s no coincidence that Blur’s second, sound-defining album was titled Modern Life Is Rubbish (or that its alternate title was Britain Versus America). The Cool Britannia movement hearkened back to the 60s and the fertile music scene it cultivated, referencing music legends such as The Jam, The Kinks, and The Who.

Blur led the way for 90s music in the UK, albeit in fierce competition with their genre-defining peers Suede, whose just-as-buzzy self-titled debut emerged in 1993. By 1994, Blur had released the seminal Parklife and a whole scene corralled around it, yielding some exceptional albums: Pulp’s quick-witted Different Class, Elastica’s indie-cool self-titled LP, Supergrass’ gleefully pop I Should Coco, and new rivals Oasis’ no-frills rock Definitely Maybe. Bad blood between Blur and Oasis infamously underscored 1995’s Battle Of Britpop, an unofficial singles competition in which both groups released a track on the same day. A modern take on mods versus rockers, the press surrounding it was nothing short of dizzying, framing it as a tug-of-war between middle-class and working-class bands.

In the end, Blur’s “Country House” outsold Oasis’ “Roll With It.” But within a year, Oasis went on to achieve staggering international fame and even broke America, which eluded Blur. This culminated in two sold-out shows at Knebworth Park, resulting in England’s largest ever outdoor concert. It was a mixed bag: the event also marked the rapid decline of Britpop, which, like grunge, had reached saturation point. Death knell theories include: Oasis’ overexposure and in-band fighting; Blur making a lo-fi album; and even the Spice Girls co-opting and diluting a Brit-centric image for global fame.

Assuming the rock’n’roll mantle

Back in the US, post-grunge acts assumed rock’s mantle by pushing the genre towards a less destructive style of brooding through longhairs such as Collective Soul, Candlebox, Goo Goo Dolls, Creed, Silverchair, and Incubus. In retort (and due to angst fatigue), an assortment of colorful ska and pop-punk acts – No Doubt, Blink-182, Green Day, and Rancid – jettisoned up the charts. Notably, the untimely death of singer Brad Nowell helped Sublime’s self-titled album move more than five million CDs by the end of the decade. There was longevity in that bright sound, which ensured success for many of those bands into the next decade.

A technological shift

Going back to 1991, there was also one pivotal music-industry development, above and beyond grunge, that indelibly shifted music tastes for decades. This was the year that Billboard updated charts to reflect actual SoundScan sales figures. Up until that point, chart rankings were determined by the projections of record-store clerks and managers. Those “guesstimations” were frequently biased in genre and did not always reflect public consumption. Doing away with that almost immediately made the charts more genre-diverse.

Teen-pop confections, a resilient market draw, never went away. Fans of Backstreet Boys and NSYNC – and, later, Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera – continued to make a significant dent in sales. And the stalwart adult-contemporary demographic made megastars out of Kenny G, Whitney Houston, Michael Bolton, and Céline Dion. Then things got interesting.

Earthier offerings such as Hootie & The Blowfish and Blues Traveler seemed to suddenly pop up out of nowhere. The runaway success of Tejano legend Selena, once relegated to the Latin world, began to pop up on mainstream charts. And Garth Brooks became an unlikely bellwether of things to come. His 1991 album, Ropin’ The Wind, released mere months after the implementation of SoundScan, marked the first time a country artist had hit No.1 on the Billboard 200 album chart.

Newcomers Billy Ray Cyrus and Tim McGraw soon followed, as did a palpable uptick in the interest of established artists (George Strait, Reba McEntire, Alan Jackson, Vince Gill, and Clint Black). And, in 1995, thanks to Shania Twain’s massive, multi-platinum The Woman In Me, country-pop became its own female-fronted genre dominated also by Dixie Chicks, Faith Hill, and LeAnn Rimes.

Hip-hop gets soulful

But Billboard’s new accounting actually had its greatest impact on R&B and hip-hop, revealing the two genres’ growing relationship with one another. The 90s kicked off with New Jack Swing in full effect, its most effective purveyors being Bell Biv DeVoe, Al B Sure, Keith Sweat, and Boys II Men. As New Jack Swing waned, R&B embraced a soul-and-groove sound typified by Janet Jackson, D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, Usher, Toni Braxton, and Mary J Blige.

But they had some competition. During the 90s, many rap acts were hitting not just the Hot 100 charts, but also Billboard’s R&B charts. This was helped by singers such as Lauryn Hill and TLC, who integrated hip-hop into their sounds. In particular, Mariah Carey’s 1995 collaboration with Ol’ Dirty Bastard on “Fantasy” became a defining moment in this crossover period in 90s music.

Hip-hop had become so pervasive because it was so dynamic; its growth spurt precipitated an intriguing assortment of subgenres. Public Enemy, Queen Latifah, Arrested Development, A Tribe Called Quest, Cypress Hill, and OutKast were waxing intellectually on social issues. And Public Enemy got alternative music’s seal of approval with Chuck D’s cameo on Sonic Youth’s “Kool Thing.” Some rappers, such as Salt-N-Pepa, MC Hammer, Coolio, Will Smith, and, later, Missy Elliot, focused on cutting anthemic jams primed for the pop charts. Others were grabbing the masses by the jugular.

When hip-hop took over

The decade started with gangsta-rap frenemies Ice Cube and Eazy-E forging their own paths, with former NWA bandmate Dr. Dre innovating G-Funk through his monumental 1992 release, The Chronic. This evolved into an epic East Coast-West Coast feud (essentially, Bad Boy Records vs Death Row Records), during which time Warren G and Nate Dogg, Puff Daddy, Jay Z, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, Busta Rhymes, Snoop Dogg, and Eminem all found fame. In fact, the latter’s Doggystyle became the first time an artist’s first album debuted at No.1. After the deaths of The Notorious B.I.G. and 2Pac, Nation Of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan held a peace summit in 1997, which ended in Cube and Common hugging it out.

Rap was little more peaceful and a lot more profitable after that. This watershed event in 90s music even primed the genre for the absolute dominance that we see today: a hip hop-led soundscape that’s a mash-up of rock, pop, and R&B. It isn’t one thing; it’s everything. And maybe that’s the true legacy of 90s music.

One-hit wonders

One last thing… As with any decade, there was also a treasure trove of one-hit wonders that arrived and slipped from the charts (at least) without a trace. Bookending the decade, you have Sinéad O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” in 1990 and Lou Bega’s 1999 smash “Mambo No. 5.” The two seemingly have little in common except large sources of outside inspiration. O’Connor’s song is arguably one of the best ever Prince covers, while Bega’s tune sampled Latin music legend Perez Prado. And no survey of 90s music would be complete without a collection of 1997 gems: Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn,” Chumbawumba’s “Tubthumping” (the “I get knocked down” song), and Hanson’s “MMMBop.” All of them may have been released in a single year, but they’ve endured far longer. – Sam Armstrong

-

Paul McCartney And Wings To Release Historic Live Album ‘One Hand Clapping’

-

Elton John Earns Multi-Platinum Plaque For ‘Diamonds,’ Shares ‘Step Into Christmas’ EP

-

Jon Batiste Announces ‘Uneasy Tour: Purifying The Airwaves For The People’

-

Best Political Punk Songs: 20 Essential Anti-Establishment Tirades