News

Big Star

There have been some great cult heroes who missed the bus to fame and glory: Syd Barrett, Kevin Ayers, Nico and others. But it’s not often you get two of them – Alex Chilton and Chris Bell – in the same group. And never a group that was both as influential and as ill-fated as Big Star from Memphis, Tennessee.

During the course of a sensationally erratic career, Big Star released four albums: #1 Record (1972), Radio City (1974) Third / Sister Lovers (1978) and In Space (2005). Each featured a different line-up and each was strikingly different, musically, from the others. Yet all of the first three albums were revered by a broad consensus of music critics, industry tastemakers and future rock stars. Mike Mills of R.E.M. summed it up when he declared Big Star’s albums “some of the best records made in that decade – they just didn’t get heard.” Robyn Hitchcock compared them to “a letter that got lost in the post.”

It’s a poignant story of a band whose immense promise was only fulfilled by those who came after them. No one in Big Star got rich. Chilton, Bell and the original bass player Andy Hummell are all dead. But their incredible legacy lives on.

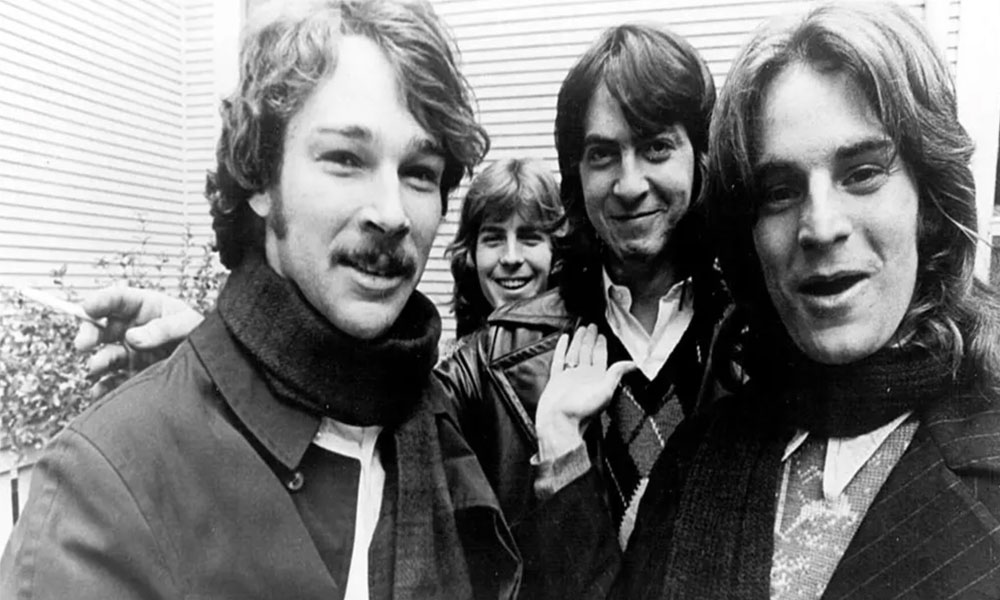

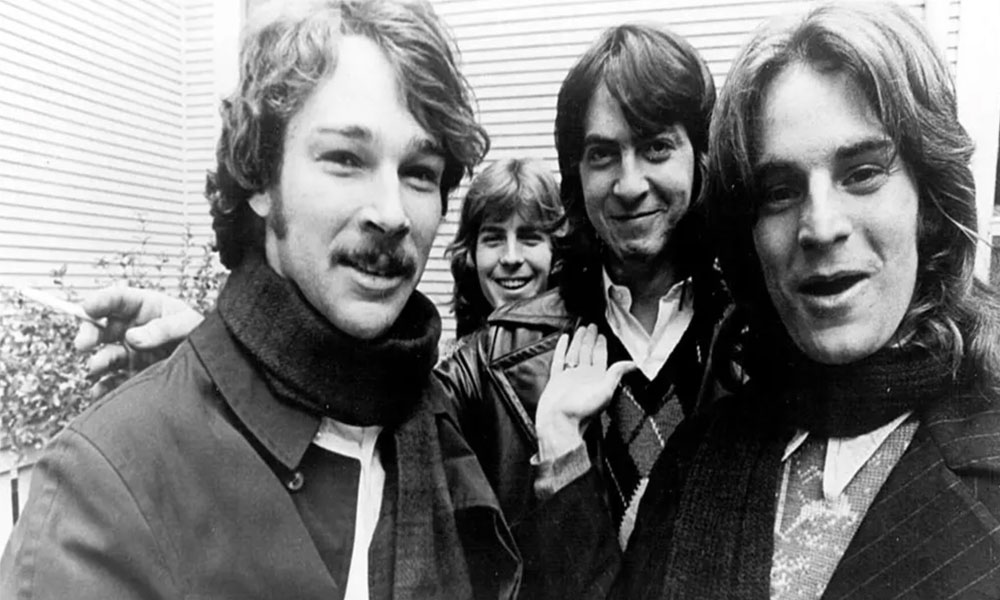

Big Star began in Memphis, Tennessee in 1971. The founding members of the group were Alex Chilton (vocals/guitar), Chris Bell (vocals/guitar), Andy Hummell (bass/vocals) and Jody Stephens (drums/vocals). Chilton, who lived his entire career in reverse, was already a rock star before he formed the band. When he was still a 16-year-old novice, the first song he ever recorded as a singer was ‘The Letter’, the debut single by the Box Tops. It became a No.1 hit in the US (No.5 in the UK) in 1967 and sold in the region of 4 million copies worldwide.

Meanwhile, Chris Bell had been writing songs and playing in local Memphis groups for much of the 1960s. In 1971, he invited Chilton to join a band he had formed with Hummell and Stephens, and Big Star was born.

There was, from the outset of Big Star, a huge disparity between the experiences and expectations of the two principals. Chilton, the charismatic frontman was the “name” musician and already something of a big star. While he had been fronting the Box Tops on TV and out on the road, playing 250 dates in 1968 alone, Bell had been one of the many struggling musicians left behind in Memphis, cleaning out swimming pools and doing other odd jobs to make ends meet. But Bell, who sang or shared lead vocals on six of the 12 tracks on the band’s first album, and co-wrote 11 of them with Chilton, regarded himself as the leader and de facto visionary of the group, a self-image which quickly became painfully at odds with public and media perceptions.

#1 Record was a seductive blend of melodic rock-guitar songs (‘The Ballad Of El Goodo’, ‘When My Baby’s Beside Me’) and sensitive love ballads (‘Give Me Another Chance’, ‘Try Again’), astutely described by their record label as “being from the same school as the Byrds, Badfinger and Todd Rundgren.” The album was greeted with a chorus of critical acclaim. “Even the prettiest tunes have tension and subtle energy to them, and the rockers reverberate with power,” said Rolling Stone. “It should go to the top,” said Cashbox, while Record World described it as “one of the best albums of the year”.

While expectations were raised sky-high, sales stubbornly refused to follow suit. The band had signed to Ardent Records, a fledgeling label attached to Ardent Studios in Memphis which had issues with its distribution operation.

While spreading the word was no problem, spreading the actual records into the shops for people to buy was more problematic.

The gushing reviews had a curiously destabilising effect on the group. Bell, still a young 21, was incensed by the way in which Chilton was assumed to be the prime mover of the group while his (Bell’s) role was marginalised to that of a sideman. “Well, you’ve done it, Alex: Your Big Star record even cuts The Box Tops’ Super Hits,” was a typical summary (by Rolling Stone). Resentment was compounded by disappointment at the commercial failure of the album, and Bell slid into a prolonged episode of depression aggravated by drink and drugs. In a fit of pique, he sneaked into the studio one night, erased the multi-track master tapes of #1 Record then went home and attempted to commit suicide. He survived, but it was the end of the line for him as far as Big Star was concerned.

Battered but comparatively unbroken, Chilton, Hummel and Stephens pressed on without Bell as a trio, and the second Big Star album Radio City was released in 1974. The band had cemented their reputation as darlings of the media by starring at the first (and last) convention of the National Association of Rock Writers – a junket attended by 140 or more journalists, and sponsored, not coincidentally, by the band’s record label Ardent.

Reviews of the new album were again ecstatic, with one critic memorably declaring it “most assuredly the finest American record since Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited”. The post-Bell line-up had pursued a more pop-friendly direction with songs such as ‘O My Soul’, ‘Back Of A Car’ and most notably ‘September Gurls’. The latter was the closest thing to a hit single that the band ever had. The song was successfully covered by the Bangles and was later ranked No. 180 in Rolling Stone’s Top 500 songs of all time.

Once again Ardent’s distributors failed to get the record into the shops in a timely fashion, if at all. Radio City, for the most part, never left the warehouse and sold a scant total of about 20,000 copies. This time it was Hummel who decided to call it quits.

The two remaining members of the group, Chilton and Stephens, returned to Ardent Studios with producer Jim Dickinson and embarked on a long, dark night of the musical soul that became the third Big Star album, known variously as Third and/or Sister Lovers.

As an essay on the numbing effect of drugs, alcohol and deteriorating relationships, it was an album with few peers. “Nothing can hurt me/Nothing can touch me/Why should I care?” Chilton sang in ‘Big Black Car’, his voice emerging from a slow, narcotic haze of guitars and a ghostly, clinking piano. In a familiar pattern, Three/Sister Lovers sold in modest quantities, but has since been recognised as a masterpiece and included in various “all-time” lists including No.1 in the Greatest Heartbreak Albums of All Time, as decided by NME.

Chilton emerged from Big Star with a personal mythology that marked him out as the cult hero’s cult hero. Bands including R.E.M., Flaming Lips and the Posies cited him as an influence while the Replacements wrote the coolest song about him – simply called ‘Alex Chilton’ – released on their album Pleased To Meet Me (1987).

Moving to New York City in 1977, Chilton briefly reinvented himself as a punk mentor. He produced the debut EP and album by the Cramps and released his first solo album, Like Flies On Sherbert (1979). He began touring again in earnest from the late 1980s and in 1993 he eventually bowed to the inevitable and reconvened Big Star. The new line-up included Stephens on drums together with Jonathan Auer (guitar/vocals) and Ken Stringfellow (bass/keys/vocals) both of the Posies. Big Star made its comeback debut at the University of Missouri music festival that year before setting off on tours of Europe and Japan. After 12 years of sporadic gigging and recording, the fourth Big Star album, In Space, finally emerged in 2005, marking the first time that any line-up of the band had managed to put out a record without immediately fracturing in some way. The album was warmly received. “In Space is no #1 Record, but at its brightest, it is Big Star in every way,” said Rolling Stone, a review which nicely summed up the consensus.

After leaving Big Star in 1973, Chris Bell went on to pursue a fitful solo career, resulting in one album, I Am The Cosmos, which was eventually released in 1992. However, long before then – in 1978 – Bell had joined the “stupid club” (as Kurt Cobain’s mother called it) of rock stars who died at the age of 27 when he crashed his car into a pole on the way home from a rehearsal.

Alex Chilton gave his final performance with Big Star in Hyde Park, London on July 1, 2009. He died in March 2010 of heart failure.

Andy Hummell returned to University in 1974 and thence embarked on a 30-year career in the aerospace technology company Lockheed Martin. He died of cancer in July 2010.

Jody Stephens still lives and works in Memphis, Tennessee.

-

Paul McCartney And Wings To Release Historic Live Album ‘One Hand Clapping’

-

Elton John Earns Multi-Platinum Plaque For ‘Diamonds,’ Shares ‘Step Into Christmas’ EP

-

Jon Batiste Announces ‘Uneasy Tour: Purifying The Airwaves For The People’

-

Best Political Punk Songs: 20 Essential Anti-Establishment Tirades